Thanksgiving, Reconsidered

By Lauren Anderson

This piece was originally published in the New Haven Independent in November 2019. Resource links have been updated slightly.

Just a few of many possible resources…

High quality books and digital content are available for use with all ages. See the list at the end of the article for suggestions.

It’s almost Thanksgiving. For the second time in two years, I received a photo of a local elementary school bulletin board full of turkeys and cherubic “Pilgrim children,” colored in crayon by first-graders. Last year and again last week, I called the school as a concerned city resident and teacher educator, asking for conversation and offering curricular support. So far, no reply.

It’s understandable that a busy administrator might neglect to return a call or two. But the miseducation of children, year after year, isn’t defensible. Our community not only has the right, but also the responsibility, to challenge the whitewashing of historical truths — yes, even for first-graders — and to demand historical accuracy.

As of a few days ago, the bulletin board in question has since been amended; thanks to those who removed the “Pilgrim children.” Undoubtedly, though, this board is not the only one of its kind.

The signposts of settler colonialism circulate in our schools as a matter of normal practice. They are the tip of a larger, deeper, structurally-supported curricular crisis, and thus call for more than surface adjustment.

Knowing this well, I’m inspired by those already teaching against the grain of Eurocentricism, “patriotic” platitudes, and U.S. exceptionalism. I am particularly heartened by youth activists who propelled legislation forward, the educators who are listening and following their lead, and the state-wide coalitions working to transform how we teach social studies in Connecticut schools. There is so much work — important, complex, hard work — to be done.

As our district embarks on a new chapter, we can and should be able to address such things in ways that are collective, constructive and humane. This begins with simple things we can do tomorrow to move away from complicity and toward greater accountability for the narratives that we allow to circulate, sometimes passively, and in so doing, teach our children.

We can take down immediately cutesy Pilgrim cartoons, along with anything else that perpetuates myths of White innocence and miseducates children by helping obscure deeper truths about US history.

We can teach more truthfully and with greater specificity – for example, that the Pilgrims in question were in fact Puritan separatists, and the Indians in question are the Wampanoag, who remain a federally recognized tribe with territories in what is currently Massachusetts.

We can teach that, even if a shared meal occurred in some form, in 1637 the English went on to massacre more than 500 Pequot men, women and children not far from where we now live and that it was very soon after that the Governor of Massachusetts Bay colony called upon all churches to celebrate a “day of Thanksgiving” for such “victories” against the Indians.

We can teach that the same celebrated President who first declared Thanksgiving a national holiday in 1863 also ordered a year later the largest mass execution in U.S. history — the hanging of 38 Dakota men for defending their people against settler aggression, murder, and forced removal from ancestral lands.

We can teach — yes, in first grade, too — about the tribes whose lands we live on. We can teach about the alternative worldviews — stewardship rather than consumption, solidarity rather than competition, reciprocity rather than accumulation, sovereignty rather than subordination — that are foundational to Indigenous education. We can teach the truth about Indigenous peoples being at the frontlines of environmental justice efforts in the US and elsewhere around the globe.

We can teach about contemporary Indigenous teachers, doctors, artists, and businesspeople, so no child ever again errs in saying, “back when Native Americans were alive.” We can teach in ways that build a sense of solidarity around shared struggle, and respect for Indigenous survivance, because our collective futures depend upon it.

Children learn as much from adult silences as they do from adult statements. It’s generally not comfortable for any of us to consider the possibility that we have gotten history wrong and/or that our “traditions” and “practices” may have been injurious to others, or may be tied up in the enduring project that is colonialism. But dealing with that discomfort is part of what it takes to unsettle “commonsense” settler pedagogies that still permeate our schools, and the society that grows outward from them.

By and large, we do not learn — or teach, really — about Native peoples because the imperatives of settler colonialism require them to disappear, and our schools, unfortunately, were meant to help disappear them. It is the perpetuation of this ignorance that educators — teachers, parents, principals, together—must work to counter or, by default, comply with. In this collaboration, conflict is inevitable, but growth is, too.

We have to start somewhere. Why not with bulletin boards? But let’s please not stop there; let’s dig in deeper and do the hard work together.

Resources for interested readers:

A Racial Justice Guide to Thanksgiving for Educators and Families compiled by the Center for Racial Justice in Education

Decolonizing Thanksgiving: A Tool for Combating Racism in Schools

Teaching Thanksgiving in a Socially Responsible Way via Teaching Tolerance

Five Ideas to Change Teaching, In Classrooms and at Home via National Museum of the American Indian

Don’t Forget Indigenous Struggles on Thanksgiving (video) with Dr. Sandy Grande (Quechua)

American Indians in Children’s Literature (blog) curated by Dr. Debbie Reese (Nambé Pueblo)

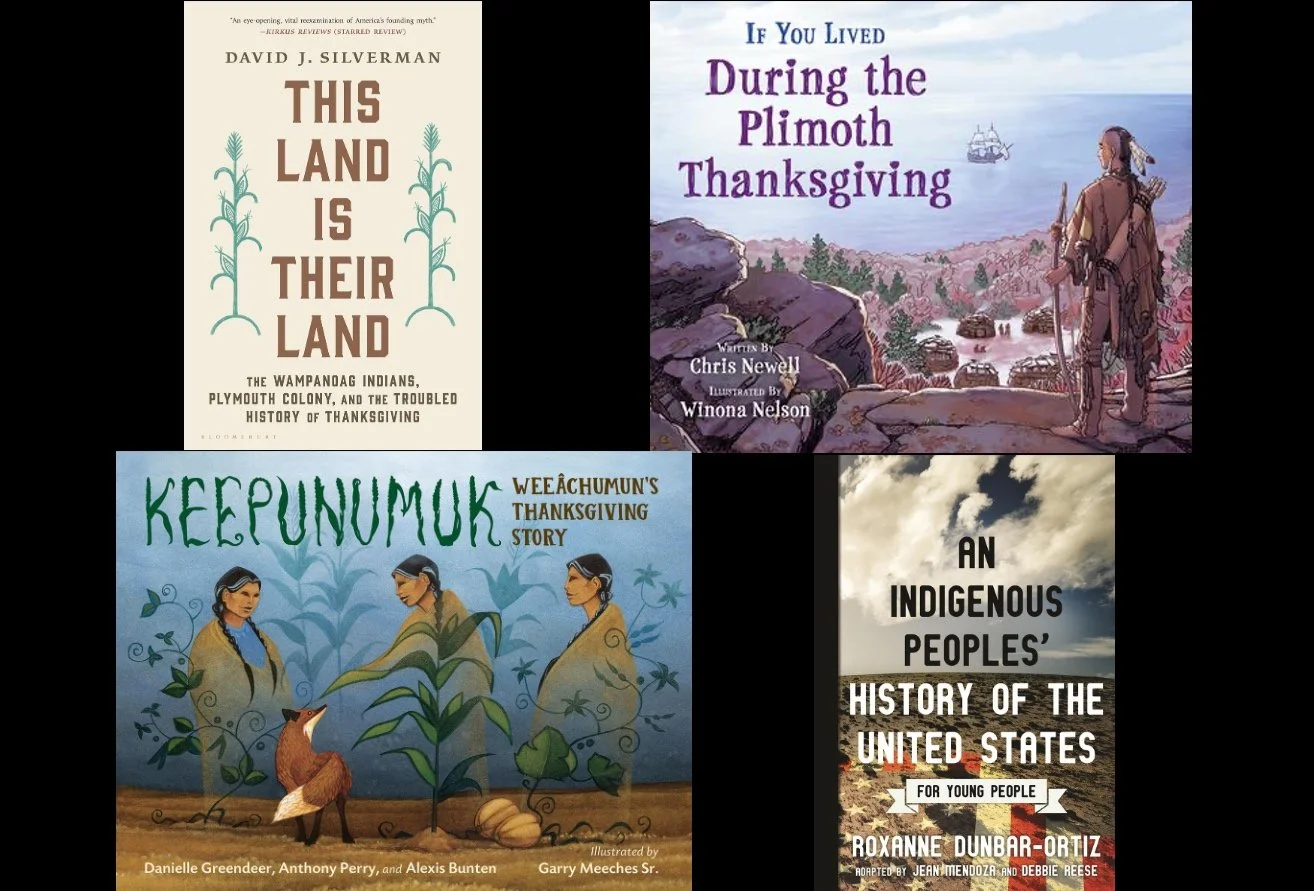

Possible Futures (community bookspace) in-stock collections for classrooms (e.g., Keepunumuk: Weeachumun's Thanksgiving Story, When We Were Alone, etc.) and teachers (e.g., Lessons from Turtle Island: Native Curriculum in Early Childhood Classrooms) (New Haven)

Akomawt Educational Initiative (Connecticut)

Mashantucket Pequot Museum and Research Center (Connecticut)

Indigenous Teacher Education Project (national)

Lauren Anderson, a former elementary school teacher, critical literacy specialist, and college professor, is the founder of the community bookspace Possible Futures and a member of the ARTLC.