Part 3: Legacies of the Black Power and Abolitionist Movements

This fourth panel depicts Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s cousin, John Huggins besides his wife, Ericka Huggins, and their child. This photo was taken from a poster by the Black Panther Party (BPP) Minister of Culture, Emory Douglas. John Huggins was a founding member of the Los Angeles chapter of the BPP after having been radicalized by his time in Vietnam, and Ericka Huggins later led the New Haven BPP chapter.

Intense repression from the police and corporate white supremacist media initially prevented the Los Angeles BPP from implementing community programs, with funds being funneled into bail, legal costs, medical care, etc at the beginning of the party’s founding. In mid-1969, the chapter was finally able to establish a community center offering political education classes and free food. They also established the Bunchy Carter Free Medical Clinic specializing in tuberculosis testing, police monitoring programs, and the Busing to Prisons program. This busing program helped families who had loved ones in the prison system still feel connected to them.

Tragically, John Huggins and fellow Panther, Bunchy Carter, were killed by an FBI-incited feud between the Black Panther Party and Ron Karenga’s cultural nationalist U.S. Organization. The FBI, under COINTELPRO, had sent fake letters between the groups to inflame tensions. At the 50th anniversary of the Fordham’s Department of African and African American Studies, Gilmore shared how her grief over Huggins’ death fueled much of her organizing: “This person was my cousin, my mother is his mother’s sister. My life changed the day he died. I was raised in an activist family. He set me on the course that brings me to the front of this room tonight.” To learn more about the Los Angeles Black Panther Party and Huggins’ work, you can access the Black Power Archives Oral History Project here.

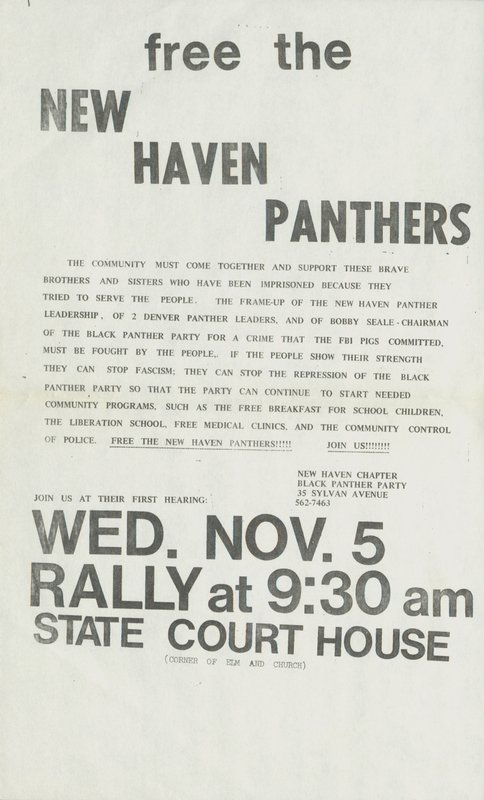

It is crucial to also recognize the powerful ongoing history of the Black Panther Party in our very own New Haven, where they established vital community programs mirroring those of the national movement. These initiatives included free breakfast programs, which ensured that children in neglected communities had access to nutritious meals before starting their school day, addressing food insecurity and promoting educational equity. Additionally, the BPP offered political education classes and community forums, providing spaces for critical dialogue, consciousness-raising, and empowerment within the community. They also set up health clinics to address the healthcare needs of residents, particularly those who lacked access to affordable medical services. Furthermore, their police monitoring programs aimed to hold law enforcement accountable for their actions and protect community members from police brutality and harassment.

Here is Yale’s Asian American Students’ Alliance statement of solidarity with the Black Panther Party in 1970

Here is an article on the rise of the Black Panther Party in Connecticut

Here is an online exhibit on the New Haven Nine and the May Day 1970 Protests

Here is an article on the New Haven Black Panther Trials